Както мнозина читатели знаят, използването на сода бикарбонат за лечение на рак беше обявено за „шарлатанска медицина“ от много говорители на официалната медицина, както и от няколко „наблюдаващи“ групи. Ето някои линкове с информация, която тотално отрича употребата на сода бикарбонат при рак.

Някои от твърденията на привържениците на содата за хляб не са съвсем точни (напр. механизма на действие). По-специално, привържениците на содата за хляб твърдят, че раковата тъкан е силно киселинна и че тази киселинна среда подхранва гъбичките, причиняващи рак. Историята разказва, че прилагането на сода за хляб алкализира тъканите и това убива гъбичките, тъй като те се нуждаят от кисела среда, за да растат. Колкото и да е странно, критиките на „разобличителите“ напълно пропускат истинските пропуски в протокола за лечение със сода за хляб и вместо това критикуват частта, която всъщност е правилна – т.е. че киселинността („ефектът“ на Варбург) стимулира рака и содата за хляб коригира тази патология.

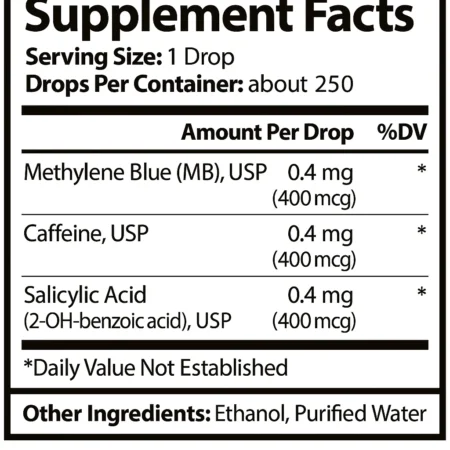

Е, действителните доказателства сочат факта, че раковите клетки поддържат силно алкална (високо рН) вътреклетъчна среда и изпомпват огромните количества млечна киселина, която произвеждат, извън клетката, като по този начин създават силно кисела (ниско рН) извънклетъчна среда. Peat е споменавал това десетки (ако не и стотици) пъти в своите статии и интервюта, като е обяснявал стимулиращите тумора (странични) ефекти на млечната киселина (например чрез VEGF/ангиогенеза, хипоксия/HIF и т.н.) и как подкиселяването на вътрешните туморни клетки бързо предизвиква апоптоза. Инхибиторите на кабоничната анхидраза (КА) са може би най-прекият подход за подкиселяване на вътреклетъчната среда на тумора, но съществуват и други подходи, като метиленово синьо, ацетазоламид, ниацинамид, тиамин и, разбира се, сода за хляб. Но раковата индустрия не може да бъде убедена в нищо и продължава да бълва идиотски нелепици за това, че ракът е генетично заболяване, а метаболитните терапии като содата за хляб са глупости.

Успоредно с официалната позиция по отношение на рака, медицинското съсловие прокарва редица медикаменти като средства за удължаване на живота и укрепване на здравето, като дори стига дотам да твърди, че някои от тези медикаменти предотвратяват рака. Може би най-известното такова лекарство е метформинът – така нареченият златен стандарт за лечение на диабет тип II. Любовта на медицинското съсловие към метформина е толкова голяма, че дори се появиха призиви всички над 40-годишна възраст да го приемат, за да се предотвратят всички хронични заболявания, които медицинското съсловие е успяло да измисли през последните 100 години. За да не останат по-назад, мениджърите от Силиконовата долина и всички видове „заети“ ( разбирайте: стресирани до смърт и силно серотонинергични) професионалисти се тъпчат с метформин като с бонбони с надеждата да предотвратят болести и дори смърт.

https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02432287

Проведеното по-долу проучване хвърля студена вода както върху генетичните твърдения, така и върху „благоприятните“ ефекти на метформина (поне по отношение на рака). Първо, то потвърждава алкалната вътреклетъчна/киселинна извънклетъчна природа на рака и показва, че туморните клетки свръхекспресират CA, който разгражда CO2, като по този начин алкализира вътрешността на клетката. Едновременно с това раковите клетки свръхпроизвеждат млечна киселина поради т.нар. ефект на Варбург. Тази млечна киселина се пренася извън клетките, което води до силно кисела извънклетъчна среда на туморната строма. Може би най-важното е, че проучването показва, че „…Извънклетъчната киселинност е необходима и достатъчна за индуцирането на кандидат-сплитинг събития“. Тези кандидат-сплитинг събития са това, което стимулира агресивните ракови фенотипове и дори първоначалното развитие на рака. Второ, той показва, че пероралното приложение на сода за хляб забавя растежа на тумора чрез ефективно подкиселяване на вътрешността на тумора (чрез повишаване на нивата на CO2) и алкализиране на външната част (чрез неутрализиране на млечната киселина). Трето, той показва, че прилагането на метформин има стимулиращ рака ефект поради способността на това лекарство да увеличава синтеза на млечна киселина във всяка клетка.

И така, ако содата за хляб е терапевтична за рак, тогава какъв е протоколът. В проучването е използвано перорално приложение на човешка еквивалентна доза (ЧЕД) от около 250 mg/kg дневно за период от 8 седмици. Това означава, че перорална доза от около 20 г дневно би трябвало да е достатъчна за повечето хора. Причината, поради която споменавам дозата от 20 г, е, че тя се оказва и най-широко използваният режим на дозиране за повишаване на ефективността сред спортистите. Ефектът на повишаване на работоспособността се постига чрез същия механизъм, с който содата за хляб е терапевтична за рака – т.е. неутрализиране на млечната киселина (млечната киселина насърчава мускулната умора) и увеличаване на CO2 (което подобрява оксигенацията на тъканите и допълнително потиска синтеза на млечна киселина).

Ето ви го, приятели. След десетилетия на абсолютна некомпетентност (а вероятно и на измама) истината бавно излиза наяве. Скоро може да се окаже, че лекарствата на баба ви (сред които се открояват аспиринът и содата за хляб) са по-силни от последните „постижения“ на медицината, дори срещу нещо толкова сериозно като рака!

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41587-019-0377-7

“…We next tested ABP-LOXCAT in a model of drug-induced acute mitochondrial dysfunction using metformin, a mitochondrial complex I inhibitor[29]. Intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 300mg kg−1 of metformin elevated the blood lactate:pyruvate ratio by 1.5-fold (P=0.0003) in 1h (Fig. 4d).”

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30755444

“…Unlike normal cells, cancer cells can adapt to survive in low pH environments through increased glycolytic activity and expression of proton transporters that normalize intracellular pH. Acidosis-driven adaptation also triggers the emergence of aggressive tumor cell subpopulations that exhibit increased invasion, proliferation, and drug resistance (4–7). Acidosis also promotes immune escape, which maintains tumor growth (8).”

“…Transcriptome-wide studies suggest that tumor stressors such as hypoxia, nutrient starvation, and lactate acidosis can each regulate gene expression at the transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels in vitro (12–14). For instance, low extracellular pH induces increased histone deacetylation, thereby influencing the expression of certain stress responsive genes and concomitantly contributing to normalization of intracellular pH through the enhanced release of acetate anions that are co-exported with protons through monocarboxylate transporters (15, 16). However, how these changes influence transcriptome dynamics is not well understood, nor is it clear whether changes in gene expression arising from such stresses in vitro also correlate with those induced by equivalent physiologic stressors in vivo.”

To confirm that pHLIP reliably labeled acidic tumor areas, we evaluated its overlap relative to two additional markers associated with low extracellular pH: expression of CA9 and of plasma membrane-localized LAMP2 (PM-LAMP2; refs. 2, 29, 30). CA9 is a major transporter that contributes to extracellular acidification through reversible hydration of carbon dioxide to bicarbonate and protons. CA9 expression significantly correlated with areas of pHLIP retention at cell membranes in both the primary tumor (Fig. 1C) and metastatic lesions (Supplementary Fig. S1D). Given the extensive overlap with, and similar patterns of CA9 expression (Fig. 1D; Supplementary Fig. S1E) relative to pHLIP positive cells in the mouse model, we used CA9 as a surrogate to label cells in acidic areas in human tumor tissues. Similar to the mouse tumors, the CA9 was enriched at tumor-stroma interfaces in human tumors (Supplementary Fig. S1F).

PM-LAMP2 indicates cellular adaptation to chronic acidosis (2, 31). PM-LAMP2 overlapped significantly with pHLIP labeled cells (Supplementary Fig. S2A) and most cells with PM-LAMP2 were proximal to the tumor–stroma interface confirming that it is acidic (Supplementary Fig. S2B). Similarly, in human IDC tumors, cells expressing CA9 significantly overlapped with cells exhibiting PM-LAMP2 (Supplementary Fig. S2C and S2D). Therefore, areas containing pHLIP labeled cells or cells expressing high levels of CA9 likely correspond to cellular areas exposed to acidic conditions in vivo.

“…To mimic increased glycolysis conditions in culture, we used metformin, a drug that inhibits the complex I of mitochondria and therefore forces excessive lactate production (44). As expected, metformin addition increased the amount of lactate in the media and acidified the media (Fig. 5C′). Metformin addition also induced the pattern of low pH-induced splicing, which were blocked by addition of HEPES (Fig. 5C). Lactate content remained increased under hypoxic or lactate acidosis conditions with or without HEPES buffering (Supplementary Fig. S5C and S5D). These results indicate that, at least for the splicing events tested, exposure to extracellular acidity is sufficient to induce the observed changes, while hypoxia-induced changes in HIF expression or increased lactate are dispensable.”

“…To evaluate the pH responsiveness of the candidate splicing events in vivo, we examined the events in tumors collected from mice that received regular or bicarbonate water. As before, consumption of bicarbonate water was sufficient to reduce tumor acidity, evident by the reduction of pHLIP-localization in cells from those tumors relative to control (Fig. 7A–A′), and to reduce lung metastasis (26). In addition, the percentage of MenaINV positive cells was significantly reduced in those tumors (Fig. 7A′–A″). To examine the pH-responsive splicing candidates in vivo, tumors from control or treated mice were analyzed by qPCR analysis. Compared with the control samples, in tumors from PyMT mice that consumed bicarbonate water the inclusion ratio of the INV exon of Mena was significantly reduced. Similarly, the DOCK7 exon 23 and DLG1 exon 6 trended toward increased ratios, following the expected directionality, however, in these cases the changes were not statistically significant (Fig. 7B). The effect of buffering on pH-responsive exons was also evaluated in a xenograft model derived from MDA-MB-231 cells. In line with the findings in the MMTV-PyMT tumors, the appearance of all candidate pH-responsive splicing events was significantly attenuated in tumors collected from bicarbonate water treated group in the xenograft model (Fig. 7C). These data indicate that alteration in the extracellular acidity in vivo directly influences the expression of the pH-responsive signature.”

“…We characterized the spatial characteristics of acidic tumor microenvironment using pHLIP technology, and demonstrated that tumor–stroma interfaces are acidic and that cells within the acidic front are invasive and proliferative. We found that exposure to low extracellular pH in vitromodulates RNA metabolism, particularly RNA splicing, and identified a potential role for a family of RBPs with affinity for AU-rich motif, in the pH-induced transcriptomic signature. The low-pH signature indicated extensive changes in alternative splicing and was notably enriched for splicing of genes implicated in regulation of adhesion and cell migration. Although the global regulation of RNA splicing in response to acidosis in vivo remains to be determined, we demonstrated that a set of functionally important candidate splicing events is similarly pH responsive in vitro and in vivo. The pH-responsive splicing of Mena and CD44 was sensitive to pH-induced histone deacetylation in vitro, demonstrating a link between chromatin deacetylation and modulation of RNA splicing in response to extracellular acidity. These findings provide new molecular insight into one way in which acidosis contributes to local transcriptomic alterations that promote prometastatic phenotypes.”

Consistent with its well established role in local invasion and malignant progression (7, 46), we found that acidosis is enriched adjacent to tumor–stroma interfaces in addition to areas within hypoxic cores. Acidosis in well-oxygenated areas can be caused by adaptation to increased aerobic glycolysis or oxidative phosphorylation (1, 47). LDHA expression was indeed enriched within a subset of acidic cellular areas at the tumor–stroma interfaces (3, 32). Acidic regions, however, were not restricted to sites of increased glycolysis marked by LDHA, indicating that acidosis may also be induced by other means such as protons generated through oxidative phosphorylation. Prolonged exposure to extracellular acidification shifts cancer cell metabolic reprogramming towards reactive oxygen species homeostasis and therefore promotes proliferation and aggressive phenotypes under harsh conditions. An example of such mechanism is mediated through a balance between histone deacetylation, mitochondrial hyper acetylation, and increased fatty acid oxidation (16). Consistently, we observed that cells within low pH areas express high levels of HDAC and Ki-67 in vivo. Our results build upon previous reports on the correlation of extracellular acidity and local growth (7) and improve our understanding of the distribution of the acidic microenvironment relative to hallmarks of tumor progression.

The inclusion of exon 19 of CD44 generates a short isoform of CD44 with a truncated cytoplasmic tail. Its expression in vitro is upregulated in multidrug-resistant MCF-7/Adr cells, and also affects cell invasion through the Ras/MAPK signaling pathway (37). Here we demonstrate both in vivo and in vitro that acidosis is necessary and sufficient to drive the expression of these isoforms in both mouse and human tumors. These examples indicate that acidic microenvironment induces the expression of isoforms of genes associated with malignancy; however, it remains to be established if acidosis in vivo induces a global transcriptomic rewiring that influences splicing similar to the phenomenon observed in vitro.

Together, our results lead us to propose that acidosis, an intrinsic feature of the microenvironment, is enriched at the tumor invasive fronts and triggers adaptive changes in gene expression and splicing that are potentially controlled through a specific set of RBPs and downstream of pH-induced chromatin modifications. Our study provides new insights into how acidosis contributes to alterations underlying malignant progression. Understanding how acidosis evokes transcriptomic changes that confer aggressive tumor phenotypes will provide therapeutically valuable insight.

Източник:

- Революционен поглед върху рака: Метаболитен, а не само генетичен проблем

- Хидроксиапатит в оралната грижа: Преглед на ползите, механизма и сравнение с флуорида

- Колко пресни портокала са ви необходими, за да изчистите черния си дроб от мазнини?

- Хроничният стрес понижава допамина и причинява психични заболявания

- Естрогенът и кортизолът, а не андрогените, потискат имунитета